Stories Unearthed from Sea to Smithsonian

From safeguarding cultural treasures to uncovering shipwrecks lost to time, Dr. Richard Kurin and Mensun Bound have dedicated their lives to preserving history. During August 2025 voyages aboard The World, these renowned scholars shared stories and insights that reveal how travel deepens our connection to culture, heritage, and humanity.

The World in Malaga, Spain.

——–

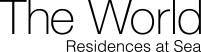

Q&A with Honored Speaker Dr. Richard Kurin

As a Smithsonian Distinguished Scholar and Ambassador-at-Large, Dr. Richard Kurin has encountered countless historical treasures around the globe. He previously served for more than a decade as Under Secretary overseeing all of the Smithsonian’s national museums, scientific research centers and educational programs, and founded the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative to help preserve endangered cultural heritage. During his recent voyage aboard The World, we sat down with him to learn more about his career highlights and how it has shaped his outlook on travel and global culture.

Your journey aboard The World took you from Siracusa, Sicily to Lisbon, Portugal. How did that influence some of your lectures?

You can’t sail the Iberian Peninsula without talking about Christopher Columbus, so my first lecture was about “Before Columbus” – exploring historical voyages in a region that has been at the crossroads of globalization for thousands of years. I’m also on the U.S. National Commission for UNESCO, and my final lecture was on the Making of Heritage Sites – giving a behind-the-scenes look on how UNESCO World Heritage Site inductions are decided upon.

What insights did you hope to impart in your lectures?

Partly, it’s to give people a framework for what they’re seeing. Of course, we all like to have lists, or keep pins in a map and collect photographs. But on The World, Residents are really committed. They enjoy a deeper dive into what makes places tick, and how scholars, scientists, historians and others interpret what they might be seeing. So, you have a deeply engaged audience, and I try to tap into that keen sense of interest.

Considering that your career has focused so much on cultural artifacts, what are some of the intangible benefits that you appreciate about traveling on The World?

In my career, I’ve dealt with everything from astrophysics and art to archeology and zoology. It’s such a range of topics, and when I travel aboard The World there are always people who are interested in those topics. Everything about this experience is wonderful, but the people – with their diverse backgrounds and interests – are what make it so special.

What experiences on land have stood out to you on this journey?

In Barcelona I’ve been watching Antoni Gaudí’s work being completed over several decades, but on this trip I was able to see Hospital Sant Pau which has been converted into a modernistic site and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. There are mosaics and murals, and fabulous exterior stonework. An architect created a design and aesthetic that is so uplifting, and from it you can understand how form can have a therapeutic function. I’ve been to Lisbon many times as the Smithsonian does work with the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation; it’s a city of cultural riches, deep history, good food, and beautiful fado music.

Hospital Sant Pau in Barcelona, Spain.

What are some of your favorite activities during your sea days on The World?

Well, it’s a wonderful space to work on my book. My wife and I wake up early to do laps in the Deck 12 pool, and we love to play bocce. We enjoy meeting with Residents over lunches and dinners, and the food just keeps coming! What amazes me is the variety; the Executive Chef and Crew really make an effort to highlight the local specialties where we’re docked. Life is pretty pleasant on board The World.

Do you still collect souvenirs when you travel?

My house is full of them. We like to be surrounded by art on the wall and cabinets of ceramics and pottery. We’ve started art cataloging things and will eventually donate to museums and organizations. It’s what we technically call “stuff.”

Well, the importance of stuff only comes from cultural context or from the person holding it, right?

Yes, you can have something that’s very mundane, but meaningful because it stands for a relationship. I still have a mug my daughter made when she was little that sits on my desk at the Smithsonian, among all these national artifacts.

You’ve just been on the front lines of so much global history. Can you pinpoint some significant experiences?

I’ve been to over a hundred countries. My first trip to India was in 1970 when I was about 19 years old. I was very naive; a New Yorker to whom going somewhere meant to New Jersey, and here I was in India and seeing the Dalai Lama.

At the Smithsonian, I started the Cultural Recovery Program. This grew out of the idea that much cultural heritage was being lost through natural disasters and human conflict. I’ve worked with Iraqis to restore the Mosul Cultural Museum– I have a long association with Haiti, working with dozens of local organizations to save 35,000 artifacts and pieces of art after the earthquake in 2010. In The Bahamas, I was part of a team that went to Abaco Island after Hurricane Dorian to save their collections. World heritage is good for tourism, but it also serves a tremendous purpose in people’s own identity.

Dr. Kurin during one of his lectures aboard The World.

How do you see The World playing a role in cultural connectedness and globalization?

Residents believe there is something to be gained by traveling the world and connecting with people. Some people learn bits of language, some dance or sing along. They take a class or attend a lecture. It’s a wonderful act of empathy. Residents are very conscious about the Earth and stewardship and the expeditions are very thoughtful. It’s a good thing, and I wish there were more of it.

——–

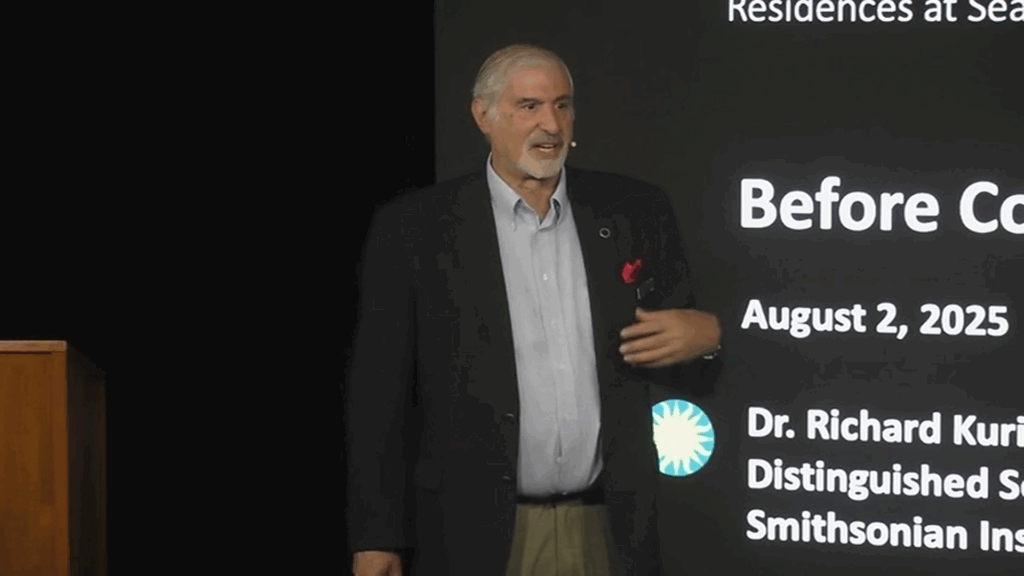

Q&A with Honored Speaker Mensun Bound

“Maritime archaeology was a way of bringing two passions together, the sea and its history.”

When some of your most life-changing adventures take place 160 feet below the sea, the ocean becomes a place you call home. We were thrilled to welcome marine archaeologist Mensun Bound on The World, bringing him on a storied route between Funchal, Madeira, Portugal and St. Helena, British Overseas Territory. While on board, he shared tales of adventures from the shipwreck excavations that have changed our understanding of maritime history and underwater archaeology.

The Colosseo room aboard The World, where residents attend lectures.

How did your upbringing spark your passion for maritime archaeology?

My family goes back to the first boatload of settlers to the Falkland Islands in the 1840s. Much of my childhood was spent in the most distant and remote part of the archipelago, and to get about we had a schooner and a ketch. These were grubby, cold, unglamorous working boats, but they gave me a love of ships and the sea. After leaving school, I signed onto an old tramp steamer that plied the South Atlantic routes between the Falklands, the River Plate, Chile and South Georgia. Much later, as a student at Oxford, I directed my first underwater excavation, and it all went from there.

Among the many notable adventures you have had in your 45-year career, can you share a standout memory?

In the early 1980s, when I was directing my own excavations underwater, I discovered a Greek pot from 600 BC painted with two combatting warriors. I was 50 meters underwater but I recognized the hand of the man who had painted it. It was a euphoric moment that cast me back over the centuries and gave me a flash of mind-touch with the ancients.

Where are some of those notable artifacts today??

Collections I have raised are on display in 13 different museums around the world, and there are many individual items in other museums. The little Greek pot came from an Etruscan wreck off the Tuscan island of Giglio. Everything from that vessel was put on exhibition at the National Archaeological Museum of Florence. These days, the contents of the Giglio wreck take up the entire top floor of the Underwater Archaeological Museum in Tuscany.

Of all the items you have recovered, what are your favorites?

That would be a gun I raised from the German “pocket battleship” Graf Spee that went down during the Battle of the River Plate. That gun is now outside the main entrance to the Maritime Museum of Montevideo. Now, as I think about it, I would have to say that my absolute favourite find was a wooden box full of books that we found in exceptionally deep water in the middle of the Indian Ocean.

Can you describe a challenging moment while searching for Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance?

The Endurance project was 10 years in the making. It all began with a friend in a South Kensington coffee shop. He came up with the idea of mounting the search and everything necessary to drive it. He wishes to remain anonymous, but he is the real hero of the story.

During that long journey there were incredible highs and lows. The worst point was during the first search in 2019 when we lost our subsea search vehicle. It was worth millions and its loss brought down the project. “Time to hang up my fins,” I said to my wife.

But then I was given a second chance and in 2022 we succeeded. We only had two dives on the wreck. The first was to secure the data, the second was the absolute high point of my life when we conducted the archaeological inspection dive. There were just four of us in the tiny control booth, and we knew we were the luckiest guys in the world. I will never forget our first view of the Endurance. We illuminated the entire stern and saw the ship’s name arching over the five-pointed steer. I have seen some amazing things on the seabed, but never anything as mind-blowing as this.

Mensun Bound aboard The World.

During your time aboard The World, you crossed between Madeira and St. Helena, the island where Napoleon was exiled. Are there any notable maritime legacies along this route?

The ocean along our route is full of shipwrecks but because of the depth the vast majority have not been found. Recently, the deepest underwater archaeological excavation there has ever been was conducted in these waters between the Canary Islands and the Cape Verde Islands.

Back in the 1990s I spent several years with the great British underwater archaeologist Margaret Rule, co-directing wreck excavations around the Cape Verde Islands. I recently returned and was gratified to find a new maritime museum on the island of São Vicente that was full of the artifacts we excavated all those years ago.

Madeira, Portugal.

Given your rich travel history, what destinations have offered you the most impactful experiences?

Oh, that is easy. Vietnam. I spent two long seasons there directing the deepest hands-on excavation there has ever been. I fell in love with the country. It was a wreck that had been found by fishermen whose nets had lost buoyancy and began dragging the seabed. Instead of fish they got pots; lots of beautiful painted pots of all shapes and sizes that had been made during Vietnam’s Golden Age of the late 15th to early 16th centuries.

The only way to work archaeologically at such a depth was to use saturation diving methods in which divers live in chambers on the deck which have been pressurized to that of the seabed, and are carried to and from the site in a dive bell which docks with the chambers on the support ship. It had never been done before and has not been done since.

We excavated over 250,000 pieces, enough to fill two huge rice warehouses. I judge a wreck by its information value, particularly new information. In that regard, the Hoi An wreck was the most important wreck I have ever excavated.

During your 45-year career, how did you balance times of extreme adventure and risk-taking with rest and recovery?

Balancing a life of high adventure with life at home was not always easy. After the success of the Giglio wreck I was suddenly on a relentless trajectory that for several decades never slowed down. I met my wife, Jo, when we were students at Oxford. She was with me on the very first day of my first wreck excavation and was with me on the very last day of my last excavation. I cannot imagine life or work without her.

I think one of the reasons why we are so close is because of some of the risks we took in our 20s. Looking back, neither of us can believe how stupid we were. Bounce diving to 80 meters on air, and so on. And yes, we had a few narrow escapes. In 1983 we both ran out of air at 50 meters when we were deep into decompression time; it was a miracle we survived. But scares like that bring you very close and make life so much more worth living.

Ready to learn more?

Determine whether life aboard The World is the right fit for you. Talk to one of our Residential Advisors today to learn more about this unique lifestyle, details of upcoming Journeys and Expeditions, and ownership opportunities.